Glimpses of the Untold History of the Indian Freedom Struggle - Part 9

हिंदी मराठी ગુજરાતી বাংলা తెలుగు മലയാളം ಕನ್ನಡ தமிழ்

Malharrao broke off interrupting the talk. He had a lump in his throat and his eyes were moist. The hearts of all present echoed more or less the same sentiment and state. But three women sitting in the corner on Malharrao’s left seemed to assume a completely different demeanour.

The first of these was Jankibai, who had completed twenty-one years of age and was in her twenty-second. ‘The very first martyr Mangal Pandey was twenty-two and so am I. How wonderful it must feel when the bullet drills into the chest! O Bhagavanta! May I be blessed with the same fate.’

The second was Kamlabai, the wife of the school master Fadke. Mature and with enough life experience behind her, she was already toying with ideas and mulling over actions she could resort to but all along, maintaining her composure.

The third woman was Govinddaji’s daughter, Sou. Manjulabai. She lived with her in-laws in the same village. Her baby, a year old, was asleep on her lap. She too was twenty-two. Assisting her father, she had been party to his conspiracies, since three years. She was a very close and dear friend of Jankibai. Her husband, ‘Vasudev Govind’ was as much a trusted and dear friend of Ramchandra Dharpurkar and as close to him as his wife was to Jankibai; and served as the human bridge between Mumbai and Dharpur. Manjulabai’s son was named ‘Mangalprasad’ – a name intentionally chosen. She was convinced that Mangal Pandey was reborn. She was convinced that it was him that she had given birth to.

The atmosphere strung with emotion seemed to ease around five minutes later. As yet a bit apprehensive, Sampatrao spoke out, “Malharrao! It is indeed very noble that Mangal Diwakar Pandey sacrificed his life but why do you refer to it as the ‘very first sacrifice’? After all Nandakumar was also hanged, wasn’t he?”

Malharrao replied, “The British resorted to deceit and treachery to hang Nandkumar, no doubt about that. But then in no way can he be called a freedom fighter. His job was to collect taxes from the Indian public on behalf of the British and he often siphoned off a portion of the collection to satiate the corrupt British officers’ appetite for luxury. Eventually, faced with dire times, Nandakumar began to stash portions of the tax collection for personal use which invited the wrath of the British, who then hanged him.

This was by no means a sacrifice in the fight for freedom. It was but a testimony of the brutal and merciless oppressive rule of the British. To hang to death, a seventy-year old man and that too for skimming off funds was definitely excessive and a matter of injustice but it does not alter the fact that it was not a patriotic sacrifice.”

Sampatrao had another question to ask. “Has even a simple stone been placed at the site where Mangal Pandey gave his life?”

Joining his hands in prayer to the Bhagavanta, Malharrao said, “After merely a month of Mangal Diwakar Pandey’s sacrifice, his close friend ‘Dhansinh Gurjar’ buried a stone of unique shape on that spot and planted the sacred ‘Tulsi’ sapling beside it. (Later, when the country became independent, a memorial in the name of Mangal Pandey was erected on that spot).

Dhansinh Gurjar held the post of ‘Kotwal’ in the Meerut cantonment. He commanded 50 soldiers. Three days prior to his death, Mangal Pandey had been in continuous contact and discussion with Dhansinh. However, Lt. Baugh issued orders of his immediate return leaving Dhansinh with no choice but to return to duty.

At the time, Dhansinh Gurjar had one sole soldier with him and so he remained calm. But within a few hours of reaching the Meerut cantonment he learnt of what exactly Mangal Pandey had managed to do in Barrackpore and incensed within, Kotwal Dhansinh Gurjar set about the mission, which had to be a tooth and nail fight. One by one, he began rallying men and finally succeeded in raising a small army of a hundred soldiers of which fifty belonged to his own unit and fifty, to other units. On 9th April 1857, the news of Mangal Pandey’s execution reached the Meerut cantonment. Almost every single soldier in the cantonment was seething with rage but what good was it? A mere forty soldiers out of the two thousand present had the gumption to join Dhansinh’s group. The rest chose to remain silent.

Out of those standing by, only thirty or forty showed the courage to hand over their cartridges to Dhansinh’s unit of a hundred and forty. But Dhansinh’s words, brilliant and stemming from the fire in him did have the desired effect and a fairly large number of cartridges could be collected. The brigade too now reached a count of 250. On 21st April came the news that Ishwariprasad too had been hanged and more and more soldiers came forward to join the mission sparking the fire of the war of independence across seven other cantonments.

The secret exchange of news and messages began. Every cantonment and post had been assigned a target.

On 10th May 1857 a fierce attack under the leadership of Dhansinh Gurjar was launched on the British officers’ post.

Spurred into action by Dhansinh’s words driven by his passion for freedom and by his heartfelt and earnest dedication, almost 600 soldiers reached Meerut urgently and armed with weapons.

The revolutionary zeal now took the common citizens from the whole of western Uttar Pradesh, Delhi, Agra, Dehradun, Bijnor, Punjab, Rajasthan, Jhansi and Maharashtra by storm. Galvanized into action, they reached Meerut armed with sickles, scythes, saws, hammers, axes and sticks to join the war of independence.

Literally thousands of the Gurjar community from villages in the vicinity of Meerut had gathered in Meerut with whichever weapon they could lay their hands on.

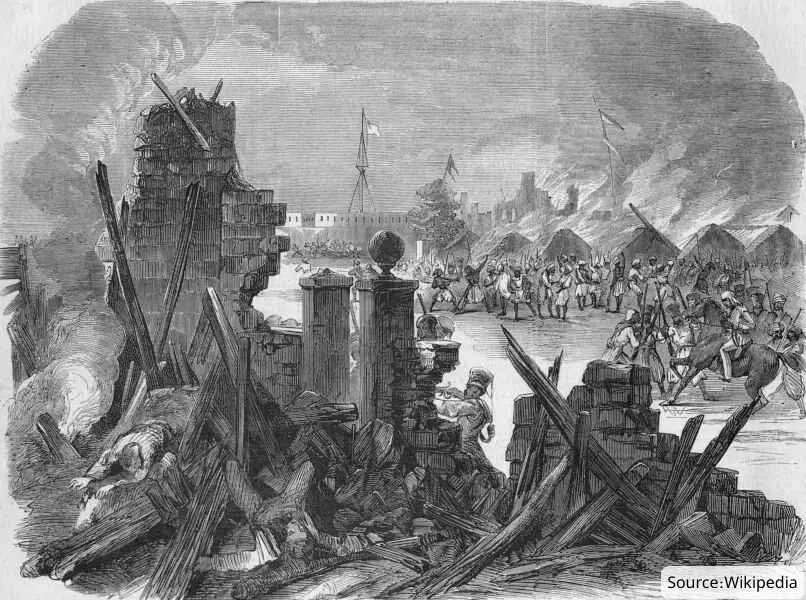

At 9 on the night of 10th May Dhansinh and his army launched an attack on the quarters of the British officers in the Meerut cantonment and made them captive. Late in the night at 2, Dhansinh’s army broke into the central jail of Meerut and set free 876 prisoners, who also joined the revolutionaries. The jail was then torched (set ablaze).

By morning twenty-two British officers and eighty British soldiers lay dead and almost as many were captives of Dhansinh.

Shouting the slogan ‘Long live the martyr Mangal Pandey!’ and armed with ordinary weapons (or even everyday tools), thousands of citizens who had swarmed Meerut from all over Bharat had burned to ashes, every building, official documents, police stations and many such assets associated with the British .

On 12th May half the army of soldiers and half of the swarm of citizens reached Delhi and the revolt spread to the villages around Meerut.

The British East India Company Government retaliated with furious attacks. Their military force was huge and their reserves of weaponry and ammunition not only abundant but also more potent and powerful.

The revolt that spread across Delhi like wild fire seemed to consume Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Bengal, Maharashtra and even Patna where similar incident were reported. The British East India Company Government was now determined, they had to crush the revolt, by fair means or foul. They were losing their grip on power. The threat was very imminent.

The British recorded victory in only a few incidents as against the freedom fighters who won in most cases. Every freedom fighter had but these three proclamations: 1) Kill the foreigner! 2) Long live the martyr Mangal Pandey! 3) Victory to the Krantisurya (the Sun of the Revolution) Dhansinh Gurjar! The skirmishes continued for three months and the British were made to bite the dust.

Ultimately (realizing that the battle on ground was getting them nowhere) the British decided to resort to deceit. They launched a brutal attack on the village (Panasli or Gagol) where Dhansinh was stationed at the time. Ten massive cannons spewed fire in the village and 500 cavalry men stormed into the village and began a mindless massacre. Thousands of men and women were butchered and the rest were hanged that too in public at crossroads.

It was here that Kotwal Dhansinh Gurjar was martyred but only after he had brought down (done in) almost a hundred British soldiers.

And it was in this very village that British laid their hands on evidence that Dhansinh Gurjar had the solid support of Rani Laxmibai of Jhansi and overnight the poor, helpless and lonely widow Rani Laxmibai transformed into a serious threat of grave magnitude.

……to be continued