Glimpses of the Untold History of the Indian Freedom Struggle - Part 7

मराठी हिंदी ગુજરાતી বাংলা తెలుగు മലയാളം ಕನ್ನಡ தமிழ்

The secret room in the Vitthal temple where Malharrao led everyone was very large. Nearly two hundred people were seated inside, yet there was no sense of crowding at all. Most importantly, the rooms used for such work in both the Shiva temple and the Vitthal temple were built to be soundproof. As a result, not a single word spoken inside could ever be heard, not even by someone pressing an ear against the wall. Above all, reaching these rooms itself was extremely difficult even for an ordinary person.

Malharrao assured everyone present that he would answer all the questions that had been put to him. Of the two hundred people gathered there, nearly one hundred to one hundred and twenty-five were between the ages of eighteen and forty. The rest belonged to the age group of forty to seventy-five were thoughtful, sensible, and patriotic individuals from their respective communities.

As soon as Phadke Master and Fakirbaba arrived there through the secret staircase, Malharrao began to speak: “I will explain everything. This is the glorious history of our motherland. However, I will not delve too deep unnecessarily. I will certainly tell you as much as is necessary for our mission.

We will, of course, study the history of the leaders of this freedom struggle. But Fakirbaba and Phadke Master will also tell you how ordinary people, over the past sixty-five years, have fulfilled their respective responsibilities in the freedom movement in various ways. For us, the common soldiers, it is even more important to understand the contribution of these ordinary citizens, for it is from them that we draw greater strength.”

Among our Indian citizens—that is, among the common masses—the British have deliberately spread several misconceptions: That it is impossible for British rule to ever be removed from this land.

That opposing the British inevitably means embracing death or facing horrific punishments such as transportation to the Andaman Islands, punishments considered worse than death itself.

That the Indian leaders of the freedom struggle do not care at all for the wives and children of punished revolutionaries, leaving them to suffer terribly thereafter.

That whatever progress India has made has been solely because of the British, and that without them India would have remained uncivilized.

This point is partly true. Even before the Queen’s rule formally began in India, it was the British who introduced railways, that is, steam train. As early as 1853, the first train ran in Mumbai from Boribunder to Thane, and thereafter the railway network spread across the country.

It was the British who started the postal department, making travel and communication far more convenient and enabling easy contact with relatives living far away.

They built paved roads, introduced motor vehicles and buses, and in cities like Mumbai and Pune, electric lighting was installed.

People no longer had to go to rivers or wells to fetch water; water began flowing directly into homes through pipes. Because of this, men and women in the cities were pleased with the British government.

Earlier, books and manuscripts were written by hand. The British introduced printing presses and offered ready-made books to everyone.

Most importantly, thousands of government jobs were created everywhere, and as a result, the livelihoods of literally millions of middle-class families became secure and comfortable.

At this point, a spirited young man of about twenty-five named Sampatrao, seated in the front rows, stood up and said, “When the British government has given us so many facilities, why should we be ungrateful toward them? Have they really betrayed us?”

Malharrao replied, “You are absolutely right. That is a perfectly valid question. All these facilities are being created by the British government primarily to ensure smooth movement of their army, to supply their forces properly with ammunition and food, and to provide ready servants and comforts for British officers and their families.

All these facilities are being funded entirely by Indian money. Not a single British pound has ever come into India.

On the contrary, the British have continued a massive loot of wealth, natural resources, gold, and silver from India for all these years, and even for that, Indian manpower is being used.

No matter how much they pretend to be civilized, the British are, in truth, thoroughly uncultured. Indians are treated in an extremely degrading manner. For these very reasons, opposing the British is necessary—and inevitable. What do you say, Sampatrao? Does it make sense now?”

Raising slogans of “Victory to Mother India” and “Victory to Bhagwan Rambhadra,” Sampatrao replied,

“This information must be spread throughout the country. People like me—those who work or study in cities—have no way of knowing these truths. Their schools, their hospitals, and the questions they raise about our religion slowly turn us into admirers of the British. We begin to accept injustice as discipline, and out of fear and forced respect, we submit to them. I am ready to leave my job in Mumbai and dedicate myself full-time to this cause.”

Seeing that everyone was now satisfied, Malharrao continued: “Initially, it was not the British government that ruled India. India was ruled by a British trading company—the East India Company. This company first established warehouses, godowns, and settlements in Calcutta, Surat, and the then-isolated seven islands of Mumbai, and then gradually began taking over Indian states systematically one after another.

At the time of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj’s coronation in 1674, the top officials of this British company behaved with extreme subservience. However, after the era of Shivaji Maharaj and Sambhaji Maharaj, the company’s desire to wield power in India grew strong, and it began finding opportunities to do so.

The East India Company bribed many rulers, certain social groups, and self-serving merchants to side with them. It also paid vast sums to the then ruler of Nepal to raise a large army, and began swallowing Indian states one by one. In 1818, the Company conquered the largest, strongest, and most powerful Peshwa state in India—after which everything seemed easy to them.

British oppression was on the rise. Even an ordinary British soldier could kick and trample a respected Indian. Discontent was slowly beginning to simmer, and some princely rulers were starting to awaken.

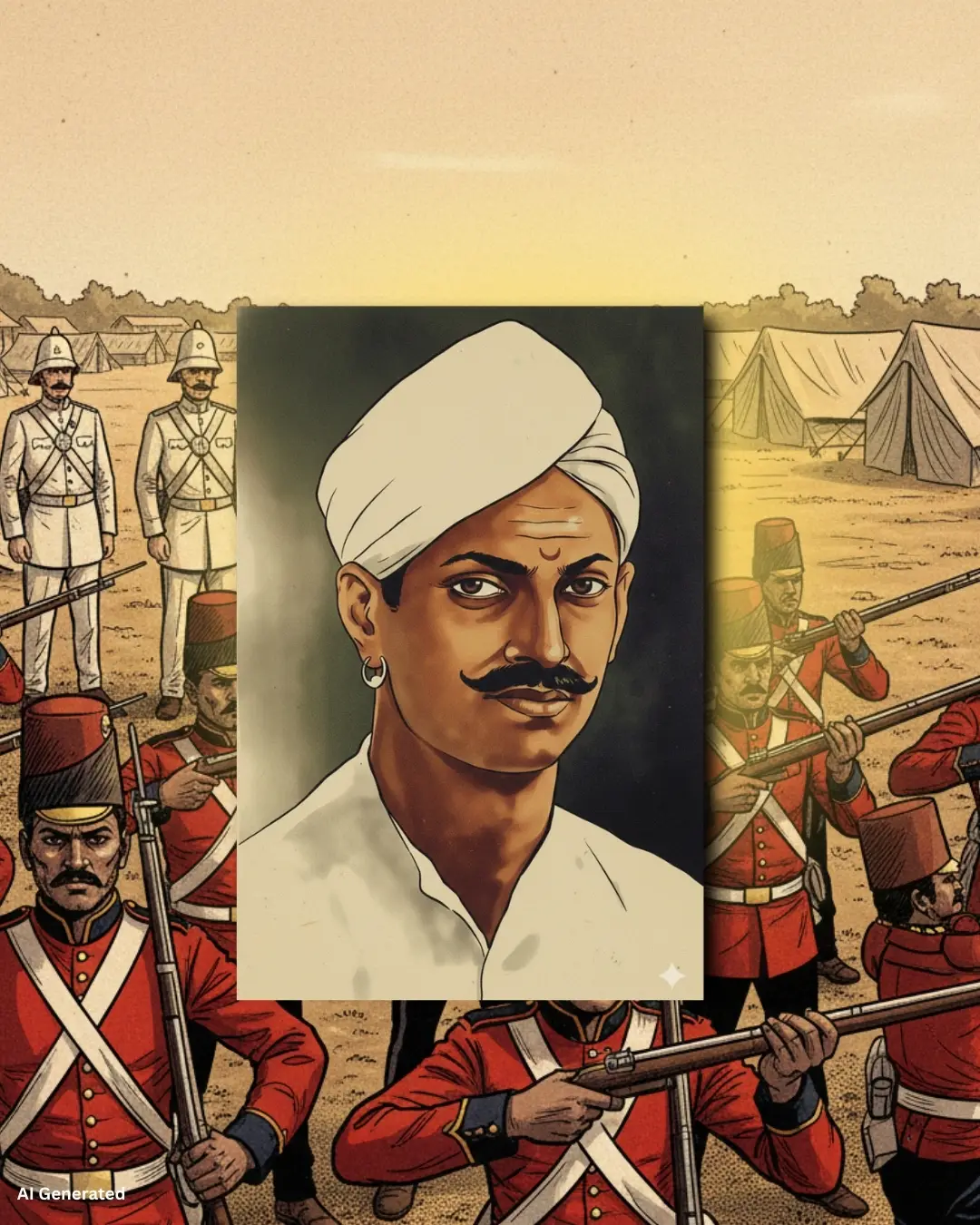

Then, in 1857, there was a British cantonment near Calcutta where the 34th Battalion of the ‘Bengal Native Infantry’ was stationed. Among its soldiers was a deeply religious Brahmin named ‘Mangal Diwakar Pandey’. In this 34th Battalion of the ‘Bengal Native Infantry’, only Brahmins were recruited.

Mangal Diwakar Pandey was the son of Diwakar Pandey, a priest from the village of ‘Nagwa’ in the Ballia district of present-day Uttar Pradesh, and he was a staunch follower of Sanatan Dharma.

This battalion was issued the ‘Pattern 1853 Enfield’ rifles—extremely powerful weapons with high accuracy. However, while loading these rifles, the cartridges had to be bitten open by teeth, and the outer casing of the cartridges was greased with fat derived from cows and pigs.

Mangal Pandey, who had a good understanding of English, learned of this in time. His deeply religious conscience rebelled. He set up a network to contact Indian soldiers of various regions scattered across the British army. Naturally scholarly and filled with courage, Mangal Pandey carefully planned his revolt and, on 29 March 1857, launched the rebellion from the cantonment near Calcutta. He received a powerful response from many places.