Glimpses of the Untold History of the Indian Freedom Struggle - Part 2

मराठी हिंदी ગુજરાતી বাংলা తెలుగు മലയാളം ಕನ್ನಡ தமிழ்

Part - 2

Writer - Dr. Aniruddha D Joshi

Ramchandra, along with two other British officers, had been searching for revolutionaries for the past two days under the pretext of inspecting the forests in that region. Naturally, Ramchandra would first contact his father before conducting any raids, and so the revolutionaries in hiding would be shifted to safer places well in advance. Earlier today, a major raid had been carried out in a neighbouring village because the two British colleagues themselves had claimed to have received a tip-off. In truth, the very plan to leak that information had been set in motion by Ramchandra’s men—who were, in fact, Malharrao’s men.

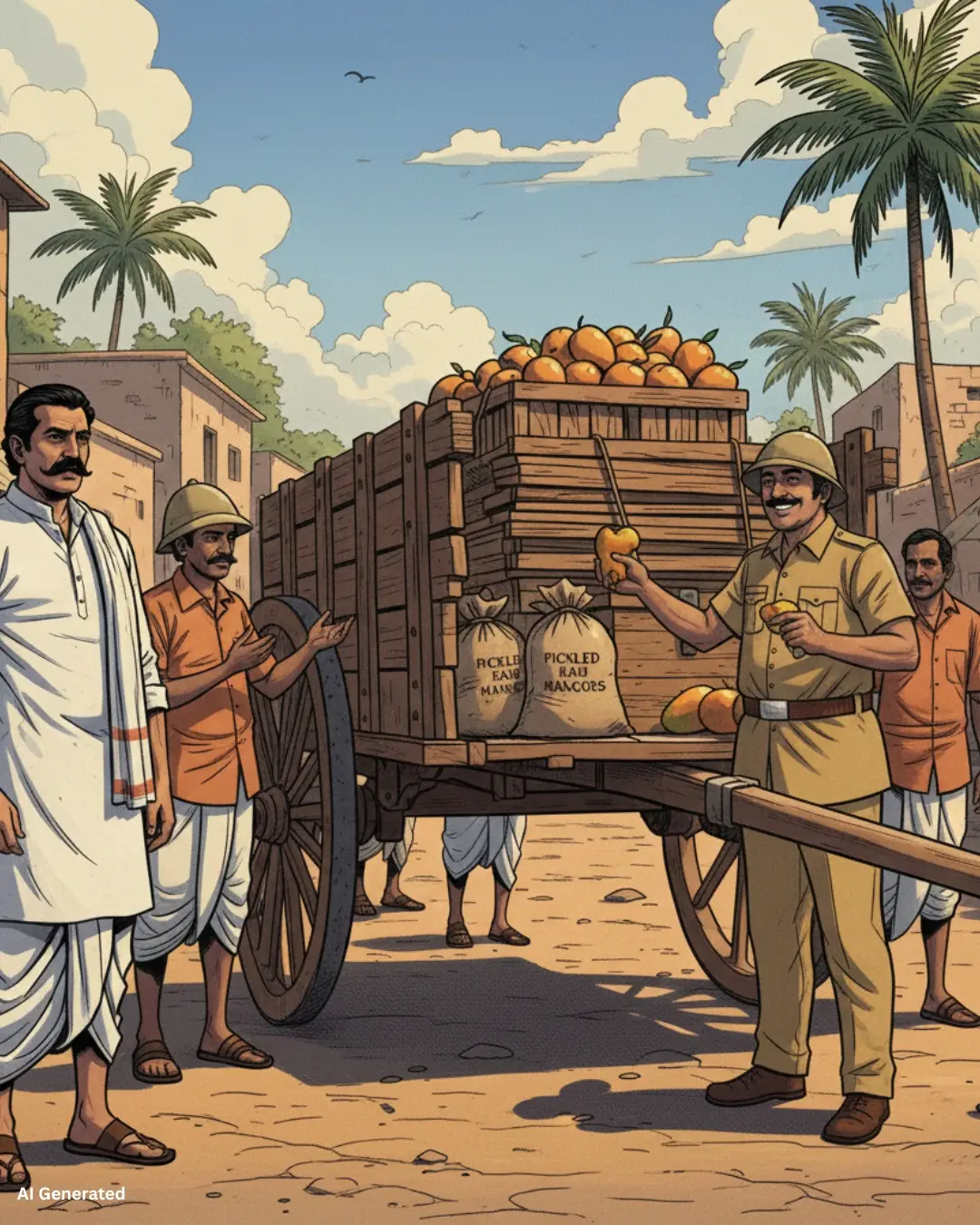

Meanwhile, in Malharrao’s own village, Dharpur, his work was progressing in full swing, right in broad daylight, and by evening everything had been completed smoothly. All the goods—pistols, small guns, cartridges and other essential supplies had already been left in bullock carts headed towards Pune. Each bullock-cart driver was himself a freedom fighter.

All those carts were filled with crates and planks of mangoes, along with small sacks full of raw mangoes meant for pickle. The real material was sent concealed behind these. At every checkpoint and outpost, every officer received either mangoes, raw mangoes, or money. The British officers in that region were well aware that Malharrao was not only wealthy in terms of money but also generous by nature, extremely loyal to the British government, and always respectful towards British officers. Thus, at every point, there was an unspoken expectation that the officer stationed there would ‘receive something or the other’.

This was not something new. Since the year 1928, Malharrao had worked systematically to establish such a reputation. On the other hand, every day, at least a hundred bullock carts set out from Malharrao’s various estates carrying some or the other goods to far-off places. The British officers, sergeants and even the Indian guards had grown tired of checking these carts over and over again. The moment they saw papers bearing Malharrao’s seal, they wouldn’t even glance at the carts again.

The worst task of all was that Malharrao’s bullock carts would often be loaded to the brim with things like firewood charcoal, sand, fine river-sand, gravelly soil, laterite stones, broken stone chips, and even cow-dung cakes. Most importantly, along with this kind of material, there would frequently be different types of gums collected from the forests. The smell and dust from all of this were unbearable—not just for the British, but even for the Indian officers and constables. At times, the carts would also contain animal hides that had been treated, as well as various kinds of salted fish. The moment the strong stench of salted fish, cured leather, or forest gum hit the air, the British officers and sergeants would literally run away from those carts.

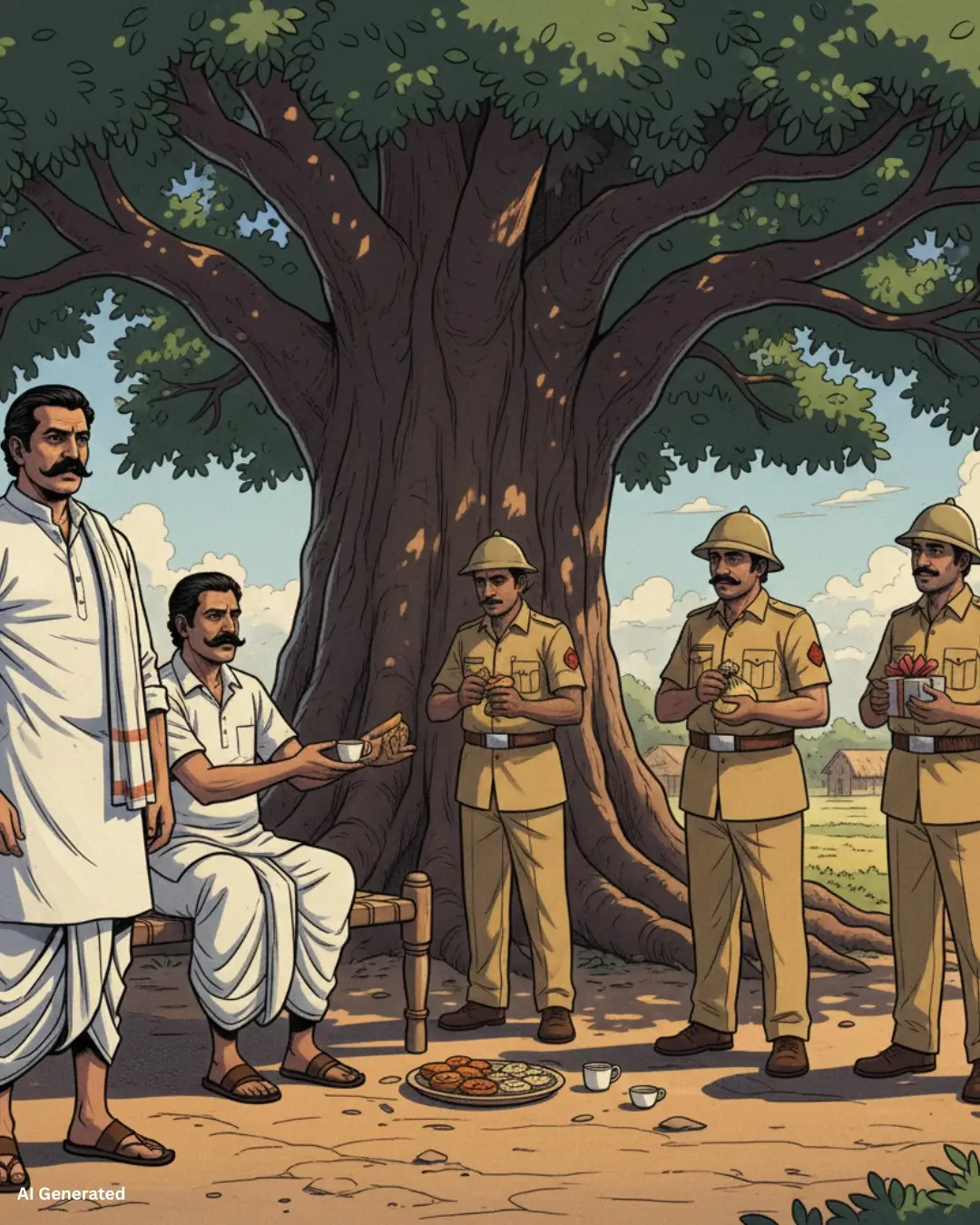

Only two or three Indian-origin constables would, out of sheer compulsion, stand there for a moment, holding their noses tightly, just long enough to stamp the papers. These Indian-origin constables were addressed by the British as “sepoys”. They were given extremely low and insulting treatment by the British; however, because they received a regular salary and several other facilities, a very large section of society was eager to become sepoys.

More than half of those sepoys had neither the awareness nor the intelligence to understand what the freedom struggle was for or what it truly meant. Most of them were uneducated or barely educated. They were angry with the British, but in order to keep their jobs for the sake of earning livelihood and also for the small pleasures it offered, they had no choice but to keep the British officers pleased. For that, these Indian sepoys would enthusiastically take the lead in beating up suspected freedom fighters.

Malharrao had spoken to Ramchandra in detail and had managed to win over many such Indian sepoys, binding them firmly to his side.

The father and son possessed immense wealth, and an equally immense determination to serve Bharatmata. Malharrao had included a few of Ramchandra’s close friends, as well as some of his own, in their secret operations. Some among them were so old that no one would ever suspect they were participants in the freedom movement.

Most importantly, Malharrao had included even elderly and middle-aged women in this work, and that too, drawing inspiration from the ideals of the Warkaris. From highly respected, prominent households to completely uneducated women from various castes and communities — all had been trained by Ramachandra’s wife, Jankibai.

When the British officers saw such elderly men, simple-looking labourers, and women from diverse communities accompanying the bullock carts, they would not dare interfere because if an old man stumbled or if any woman from an esteemed family was insulted, the entire society might turn against the British. To prevent such a situation, the officers frequently received strict warnings from their superiors. Because of this, Malharrao’s and Ramachandra’s operations ran absolutely smoothly.

On top of that, Malharrao was deeply religious. British officers knew him only as a wealthy zamindar who had been always chanting God’s name. Among themselves, these British officers would refer to Malharrao as “a cunning old man who commits all sins and prays to God only to reach heaven afterward.”

There were two reasons for this:

Malharrao would renovate temples in various places, even in the smallest of villages. He regularly visited temples and made generous donations. He had also built wells and small dharmshalas near many temples.

On the other hand, he never failed to attend the tamasha performances at every village fair, and lavani programmes were often held openly in his mansion — many times, quite frequently.

In truth, Malharrao had absolutely no interest in such programmes, but he had to put on an act of flamboyance. These displays were necessary only to make the pleasure-seeking British officers warm up to him and seek his friendship.

Among the British, Ramachandra was known as “Ramachandrarao” or “Dharpurkar Saheb.” His wife, Jankibai, too lived in a manner befitting the wife of a high-ranking officer. She was known throughout Mumbai and Pune as “the most fashionable lady.” Her social circle consisted entirely of British officers and their families, wealthy Parsi women, and the wives of Indian officers loyal to the government.

Jankibai was only twenty-one, but people of that time were fascinated by her because she spoke fluent English. The Governor’s wife was her close friend. In fact, the Governor’s wife would never attend any function without Jankibai by her side.

As soon as Malharrao received word that the carts had safely reached their destination, he set out towards the timber depot and the charcoal kilns situated on the outskirts of the village. Because there was always smoke and dust in that area, the villagers rarely passed that way.

However, the entire village knew very well that right in front of that depot stood the Dharpureshwar Mahadeva temple, which Malharrao had restored (in truth, rebuilt entirely). Inside the temple, along with the Shiva Lingam, there was also an idol of Trivikrama in his Hari-Hara form.